Epitheory

I have come to believe that an exhibition is not merely a space in which art is displayed, it is a threshold, an unfolding, a site where narrative, architecture, and human cognition meet. Over the course of more than thirty exhibitions around the world, I have been developing a framework I call Epitheory: a practice that treats the art exhibition as a vessel for lived experiences and psychological experimentation; an opportunity where the role of the artist extends beyond creation and into orchestration. In this view, art is not confined to canvas or wall; it becomes a total environment, an act of storytelling transmitted through spatial logic, sensory cues, and the choreography of the viewer’s movement.

Epitheory emerged organically, long before I had a name for it. Each exhibition became an attempt to capture an idea so large or so layered that only a multisensory experience could give it shape. I came to utiliyze entryways as prologues, lighting as syntax, sound as subtext, and the arrangement of paintings as the cadence of a contiguous rhythm produced from the frequency my brain conducted. The objective was never to impress an audience with the spectacle of art, but to immerse them in a narrative atmosphere so resonant that it lingered quietly, insistently long after they departed. In this way, the exhibition became a carrier of memory: a temporary world built to imprint a lasting story.

At its core, Epitheory is the pursuit of durable meaning. It asks whether an exhibition can function as a mythopoetic engine, an experience that generates stories people feel compelled to retell. I have always believed that if a show dissolves the moment its walls are struck, then it has not yet fulfilled its potential. What matters is the conceptual afterlife: the ideas that survive the closing, the emotional residue that travels from viewer to viewer, transforming in the retelling like a folktale carried across generations.

This article serves as both a record and a theoretical mapping of that pursuit. It traces the evolution of Epitheory across the exhibitions that shaped it, each one contributing a unique articulation of its guiding principles. These projects span continents, cultures, and moments in life, yet they share a common ambition: to elevate the exhibition format beyond presentation and into the realm of experiential philosophy.

In the pages that follow, I will examine each exhibition not simply as an event, but as a chapter in the ongoing development of a larger idea an idea I believe will continue to grow, be challenged, and perhaps even formalized by artists long after me. If these shows have taught me anything, it is that art’s most enduring power lies not in the image, but in the experience it orchestrates and the stories it inspires. Epitheory is my attempt to honor that power and to push it further.

—

The Red Door Gallery, The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

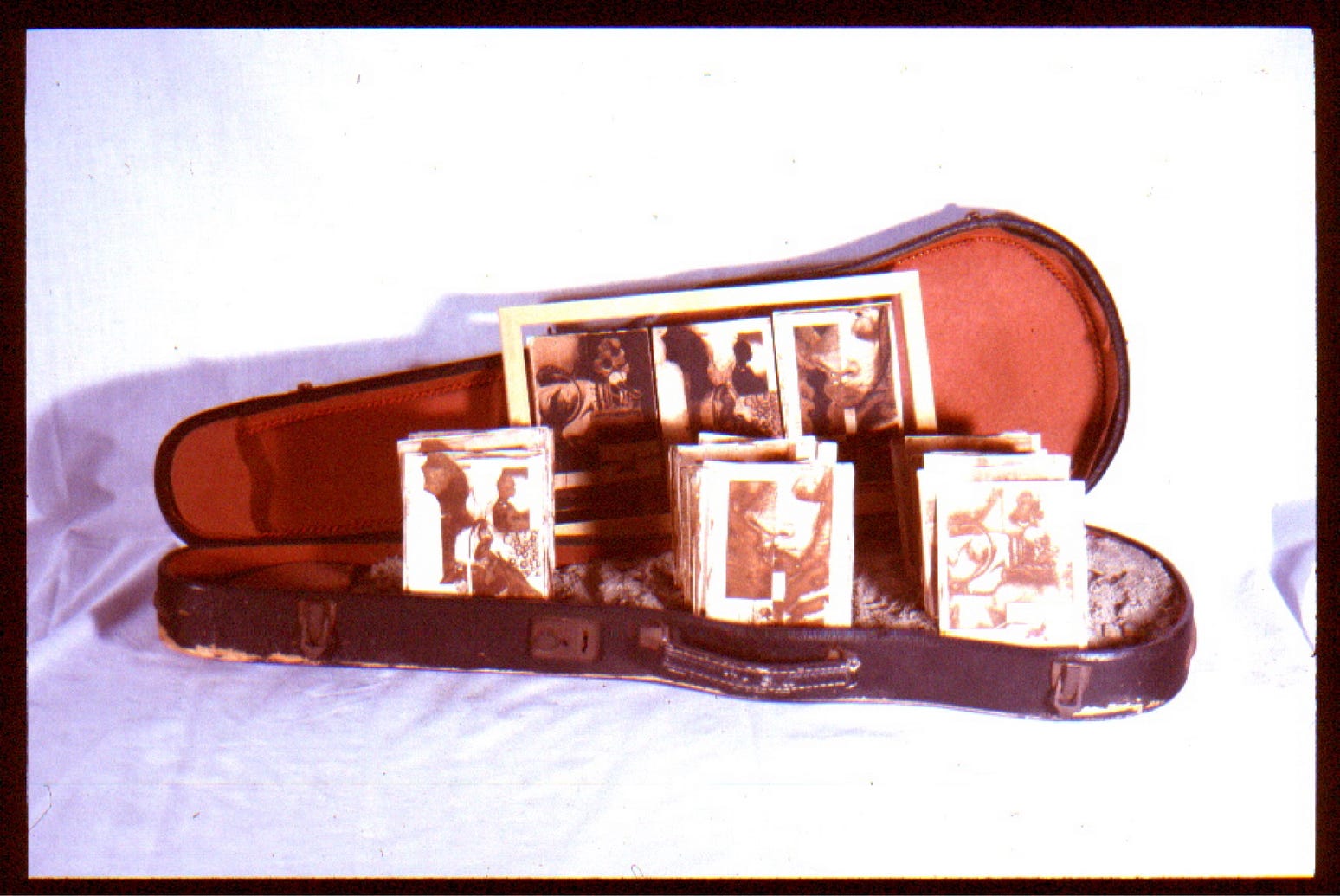

The first solo exhibition I ever had was at The Red Door Gallery marked not only an unusual honor within the institution’s history, but also the quiet beginning of my lifelong inquiry into authorship, perception, and the performative dimensions of the artist’s presence. The show was built around a deceptively simple intervention: a red leather wingback chair placed at the center of the room, a pedestal table of award-winning sketchbooks, and a series of works displayed without the artist’s name appearing on any promotional materials. In a gesture of generosity and subversion I had created 200 original prints and mailed them to professors and strangers alike, ensuring that the exhibition began not in the gallery but in the homes and hands of the audience themselves. This democratized form of invitation transformed the viewers into participants before they ever stepped into the space; many brought their mailed prints with them, effectively collapsing the boundary between promotion and artifact, and making the audience’s journey into the exhibition part of the work itself.

The psychological richness of the exhibition emerged most vividly on opening night, when an elderly collector (one of my patrons) took a seat in the wingback chair and leafed through the sketchbooks. Because the exhibition lacked any identifying authorship, attendees naturally assumed he was the artist. Rather than correcting them, I receded into the periphery, listening as strangers evaluated the work with refreshing candor. This misidentification transformed the event into a living experiment in identity construction, perception bias, and the dramaturgy of the gallery space. By allowing another body to become the locus of authorship, I unintentionally exposed how readily audiences project meaning onto perceived authority, age, and demeanor. I would later come to believe that the installation became an exploration of Erving Goffman’s “front stage/backstage” dichotomy, a reversal in which the true artist occupied the shadows and the guest inadvertently performed the role of the creator. This experience fundamentally shaped my understanding of how artist identity can be intentionally destabilized, manipulated, or withheld to heighten narrative tension within an exhibition.

—

Big Umbrella Gallery, San Francisco: The Pseudonym Experiments

Building on the revelations of my first exhibition, my tenure at Big Umbrella Gallery became a laboratory for the deliberate fragmentation of artistic identity. Rather than presenting myself as a single artist with a cohesive body of work, I dissolved into a constellation of invented personas, each with its own visual language, biography, and philosophical stance. These fictional artists were made vivid and believable through Vandal Magazine, a publication I created to give them voice, visibility, and a shared cultural ecology. In the early years of social media, I extended the experiment further by crafting full digital lives for these personas — Facebook pages, Twitter handles, and even standalone websites. The gallery became a stage for a fictional collective that the public had no reason to doubt, precisely because the digital ecosystem validated their existence. This was an early, prescient exploration of how narrative infrastructure can legitimize identity in contemporary culture.

Psychologically, the exhibition was a complex investigation into authorship, multiplicity, and the performative construction of credibility. By having my pseudonyms publicly critique one another (sometimes fiercely) I staged a meta-discourse on artistic superiority, aesthetic ideology, and the tribalism that forms around style. Viewers became unwitting participants in a social experiment echoing the work of G.H. Mead’s theory of the “social self,” where identity is co-created through interaction, conflict, and public performance. When the online debates escalated to a feverish 128 public responses, I revealed that every voice in the argument had been my own. This revelation destabilized the audience’s assumptions about authenticity and underscored the degree to which credibility is a psychological construct, shaped less by truth than by narrative cohesion and performative confidence. In retrospect, this exhibition foreshadowed our era of digital multiplicity and AI-generated identities , demonstrating how easily the boundaries of authorship can be blurred, expanded, or ruptured.

⸻

Love Gallery, Denver: The Proxy Artist Experiment

AtLove Gallery in Denver, my ongoing exploration of artistic identity entered a new and theatrically daring phase. Invited through Instagram and asked to attend both the opening and closing of my solo exhibition (without any budget for travel or lodging) I devised a solution that transformed logistical constraint into conceptual opportunity. I shipped the artwork as requested, but instead of arriving in person, I hired an actor from the University of Denver to portray me. Equipped with a carefully crafted script, my biography, and the behavioral cues of how you typically navigate openings, he stepped into the role of “Harrison Love” with me shadowing the event remotely through texts and calls. The gallery attendees, enchanted by the work and lulled by the conventions of opening-night etiquette, accepted him without question. The show succeeded by all metrics, and the gallery owners were delighted, unaware that the artist they had hosted was, in fact, an embodied fiction.

Psychologically, this exhibition was a profound demonstration of persona substitution, parasocial expectation, and the cultural passivity of gallery audiences. By placing a trained actor into the role of the artist, I exposed how little the public actually demands of authenticity in performative spaces, reaffirming Judith Butler’s assertion that identity is not fixed, but iteratively enacted. The actor’s account afterward, that this was the first time he had played a character responsible for “setting the world,” underscored the uniquely generative power of artistic authorship as a psychological state. Moreover, the success of the ruse revealed a cognitive bias frequently at play in art environments: spectators tend to project authority and authenticity onto any individual positioned as the artist, especially when mediated by aesthetic awe of my paintings. Unlike deception aimed at manipulation, my intent was both practical and conceptual; folding the event itself into the artwork, foregrounding the constructed nature of presence in contemporary art rituals. When the actor disclosed the truth to the gallery during the closing, no apology was needed; instead, they expressed admiration for your creative problem-solving, validating the experiment as an elegant extension of my ongoing inquiry into artistic identity.

—

Persona Gallery, DUMBO: The Great Unmasking

The final chapter of the long-running identity experiment unfolded at Persona Gallery in DUMBO, a fitting venue for the culmination of a practice rooted in multiplicity, illusion, and narrative construction. Over many years, I had maintained the social media lives of several fictional artists, each persona evolving alongside the shifting landscape of digital culture. This exhibition became the moment of revelation: a controlled dismantling of the mythos I had built. Before disclosing the truth, however, I conducted a deliberate stress-test of the algorithmic ecosystem itself, using myt pseudonyms as instruments to expose the behavioral incentives embedded within social media platforms. The gallery served as both archive and stage, presenting the accumulated identities in parallel with the digital evidence of their reach, thereby collapsing the boundary between the physical exhibit and the sprawling, years-long performance that had taken place online.

Psychologically, the exhibition functioned as a profound inquiry into algorithmic aesthetics, behavioral engineering, and the commodification of persona. This controlled experiment revealed that the algorithms consistently rewarded two primal human triggers: eroticism and outrage. The persona that embodied the most theatrical, wounded, or chaotic emotional register became the most algorithmically amplified, achieving 2.7 million views on TikTok and a staggering 40,000% spike in Instagram reach. This was an embodied demonstration of Paul Ekman’s research on emotional contagion, as well as Jonathan Haidt’s work on moral outrage as a viral accelerant. By unveiling the truth, that a single artist had authored every identity, I simultaneously exposed how easily digital culture mistakes performance for authenticity and how profoundly algorithms shape public perception. The exhibition’s unmasking became a mirror held up to the audience, revealing how identity in the digital age is less a stable construct than a feedback loop shaped by visibility, reward systems, and the emotional heuristics of the crowd.

⸻

Exploring Concepts of Social Relevance, Socio-Economic and Political Art

—

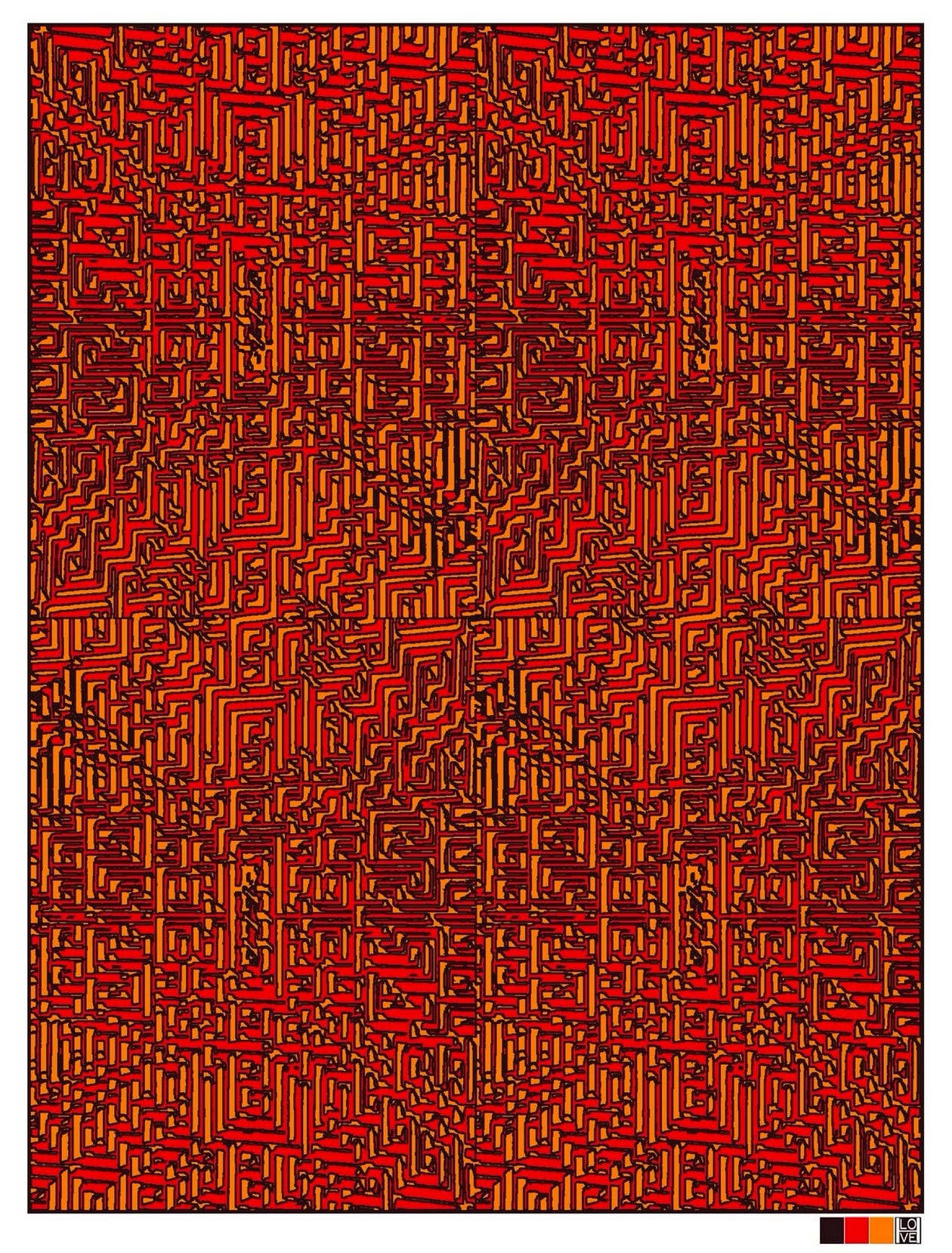

RIND — John Erdos Gallery, Singapore

RIND marked a pivotal moment in my exhibition history, breaking sharply from the aesthetic and cultural expectations of Singapore by introducing a visual language rooted in American graffiti; an art form strictly outlawed in the country. Installed in place of the preceding Keith Haring exhibition, RIND positioned my work within a lineage of artists who challenge the limits of sanctioned expression. The show explored the metaphor of the “RIND” as the tough, bitter exterior that protects the sweetness within, suggesting that the parts of culture considered abrasive, illegal, or socially unpalatable often hold the richest forms of truth. By bringing a forbidden artistic dialect into a formal gallery setting I reframed illegality as a lens for deeper understanding, asking viewers to reconsider where value and intellectual nourishment truly reside.

Psychologically, the exhibition invoked principles of neuroplasticity, cognitive dissonance, and aversive reward, the idea that difficult, disfluent, or even uncomfortable stimuli can stimulate deeper cognitive engagement. Research shows that when viewers confront images that violate their expectations or challenge cultural norms, their brains shift into heightened processing modes, forming stronger synaptic connections and more lasting impressions. In a society where graffiti is criminalized (as is the case in Singapore), the very act of viewing such marks inside a gallery created a productive psychological rupture: a moment where discomfort transformed into insight. RIND therefore became a neurological encounter as much as an artistic one a curated instance of “bitter beauty” engineered to stretch perception, rewire assumptions, and reinforce the idea that intellect, like fruit, must sometimes be nourished by what lies beneath the surface.

—

RED RUM — The New School Gallery, Singapore

Red Rum unfolded at this same intersection of cultural censorship, cinematic mythology, and psychological tension, staged in Singapore on the 50th anniversary of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (a film still prohibited from screening within the country) several works in the exhibition referenced iconic scenes and symbolic motifs from the film, prompting the Singapore Censorship Bureau to intervene. For the first several hours of the exhibition, the gallery doors remained closed as officials photographed, inspected, and selectively approved individual pieces. This atmosphere of controlled scrutiny became an unplanned, yet potent extension of the show itself. Red Rum was no longer merely an homage to Kubrick, but a live negotiation between artistic intention and institutional authority, revealing how influence survives, even thrives, when placed under pressure. In choosing ultimately to exhibit the full suite of works, we reframed censorship as a psychological aperture: not a limitation, but a heightened state of awareness.

Thematically, Red Rum activated key psychological principles such as forbidden-fruit cognition, arousal theory, threat-based attention, and neuroplastic dissonance. Research shows that when material is restricted, controversial, or formally prohibited, the brain assigns it increased salience, triggering deeper processing and stronger memory encoding. The tension between what the audience was “permitted” to see and what was culturally taboo transformed the viewing experience into a cognitive event, one charged with uncertainty, hyper-focus, and a sense of transgression. Kubrick’s original film is itself a study in psychological unease, leveraging ambiguity, pattern-recognition stress, and symbolic suggestion to keep the viewer in a state of unresolved cognitive engagement. This exhibition replicated these neurological dynamics through visual form, while embedding them in the lived context of censorship. Thus, Red Rum became a dialogue about the elasticity of artistic influence in restrictive environments, and a testament to how constraint can paradoxically expand perception, deepen introspection, and fortify the neural pathways through which art reshapes the mind.

⸻

BEYOND THE STREETS — Los Angeles & California (Collaboration with Shepard Fairey and Others)

Myinvolvement in Beyond the Streets marked a decisive pivot into politically charged artistic terrain, aligning my work with a lineage of street artists, most notably Shepard Fairey, whose practices fuse visual language with civic intervention. Unlike traditional gallery settings, Beyond the Streets intentionally dissolved the boundary between institutional space and the public realm, spreading large-scale installations across remote locations and inviting audiences to discover art in lived, urban environments. This was a return of imagery to its natural habitat: the street, where graffiti and counterculture aesthetics were born as acts of visibility, protest, and self-definition. The exhibition reframed art not as an object to be entered, but as a landscape to be navigated; expanding the viewer’s role from passive observer to urban explorer. In taking art outside the curated safety of the white-walled gallery, the show summoned the political roots of graffiti and reasserted creative expression as a public right rather than a privatized luxury.

Psychologically, participation in Beyond the Streets activated principles of public cognition, territorial aesthetics, collective identity, and embedded narrative processing. Research in environmental psychology shows that unexpected artistic encounters in public space heighten emotional response, increase memory retention, and generate stronger feelings of agency and belonging. Graffiti, once dismissed as vandalism, emerges here as a democratizing force that disrupts predictable visual routines and engages the brain’s orientation and novelty-detection systems. By working alongside artists who built their careers on semiotic rebellion, I joined a community that uses imagery to challenge systems of authority, ownership, and public visibility. The exhibition leveraged the psychological power of scale, location, and social participation to reawaken political consciousness, underscoring that art is not merely something to be viewed but something to be lived through, a civic gesture that rewires how people move through, perceive, and psychologically occupy their cities.

⸻

RIOT / PROTEST SERIES — The SUB Gallery, San Francisco (2015)

The Riot exhibition at The SUB Gallery marked a new epoch in my practice, one in which aesthetics evolved into active political instrument. Rather than simply representing unrest, the paintings sought to embody the sensory and psychological charge of public protest: the adrenaline of collective movement, the disorientation of tear gas and chant, the oscillation between fear and solidarity. These works were not depictions so much as emotional proximities, attempts to render the lived intensity of dissent at a moment when the United States was beginning its slide toward heightened authoritarian rhetoric. Alongside the paintings, I devised an innovative narrative-capture method using repurposed smartphones placed at real protest sites. Protesters recorded testimonials, micro-interviews, and ambient soundscapes, producing an archive of lived resistance that played within the gallery. This interweaving of painting and protest-story data created a multi-vocal installation, part memorial, part documentation, part rallying cry. The exhibition also marked an institutional breakthrough: it was during this period that my work was collected by the SFMoMA Artist’s Gallery, signaling recognition of the political force embedded within my visual language.

Psychologically, the Riot exhibition engaged mechanisms such as collective effervescence, empathic arousal, communal narrative encoding, and agency restoration. Social psychology shows that participating in collective action activates neural circuits associated with empowerment, shared identity, and moral alignment. By placing real protest narratives within the gallery, the exhibition created a feedback loop in which viewers experienced protest through both visual abstraction and human testimony, strengthening empathic engagement and motivational contagion. The chaotic mark-making of the paintings mirrored the neurological signatures of protest itself: fluctuating attention, heightened threat perception, and rapid emotional appraisal. In essence, Riot functioned as both representation and rehearsal, a space where the psychological architecture of resistance could be felt, studied, and internalized. This phase of my career revealed art’s potential as counter-propaganda: not through coercion, but through the reactivation of agency, critical awareness, and the memory of collective power.

⸻

Mural of Possible Futures — Dolores Park, San Francisco

Itwas during this era of my Career that I was commissioned to create The Mural of Possible Futures at Dolores Park, which represented a major public articulation of your political and ethical philosophy, expanding your exploration of collective action into a large-scale civic narrative. Positioned in one of San Francisco’s most historical and culturally symbolic locations, the mural presents a crossroads, an allegorical tipping point between two potential trajectories for society. One path depicted the accelerating descent into authoritarianism, hyper-individualism, and passive obedience to deteriorating power systems. The other path imagined a reawakening of communal responsibility, ecological stewardship, and cultural vitality. Mind you this was years before the Covid Pandemic would in many ways serve to foist individualism and isolation upon our society. The mural operated simultaneously as a warning and a proposition: a visual manifesto encouraging San Franciscans to re-examine their complicity in the passive consumption of media, technology, and political spectacle. Situated in a park long associated with bohemians, musicians, activists, and the city’s queer and artistic heritage, the work challenged the ongoing erasure of San Francisco’s cultural memory at the hands of tech-centric development. It reminded viewers that the future is not merely unfolding, but is continuously authored by collective choices or by collective negligence.

The mural engaged principles of future-oriented cognition, moral reframing, social dilemma theory, and cultural grief. By presenting two divergent futures side-by-side, the work activated the brain’s episodic future-thinking system, prompting viewers to simulate potential outcomes and evaluate their own role in shaping them. The mural’s dichotomy echoed the classic “tragedy of the commons,” inviting reflection on how individual short-term incentives, comfort, convenience, passive consumption can undermine long-term communal flourishing. It also addressed the emotional dimension of cultural change: the grief, disorientation, and nostalgia that arise when a community senses its heritage slipping into obscurity. Public art researchers note that murals can serve as anchors of identity, stabilizing collective memory while stimulating civic agency. In this case, your mural functioned as both a cultural mirror and a moral provocation, urging citizens to reclaim their responsibility as tenants not owners of the future. Through its heightened visibility and symbolic placement, The Mural of Possible Futures became a site of cognitive reckoning: an invitation for viewers to interrupt passive trajectories and consciously redirect the arc of their shared destiny.

⸻

Exploring concepts of full immersion and audience participation

⸻

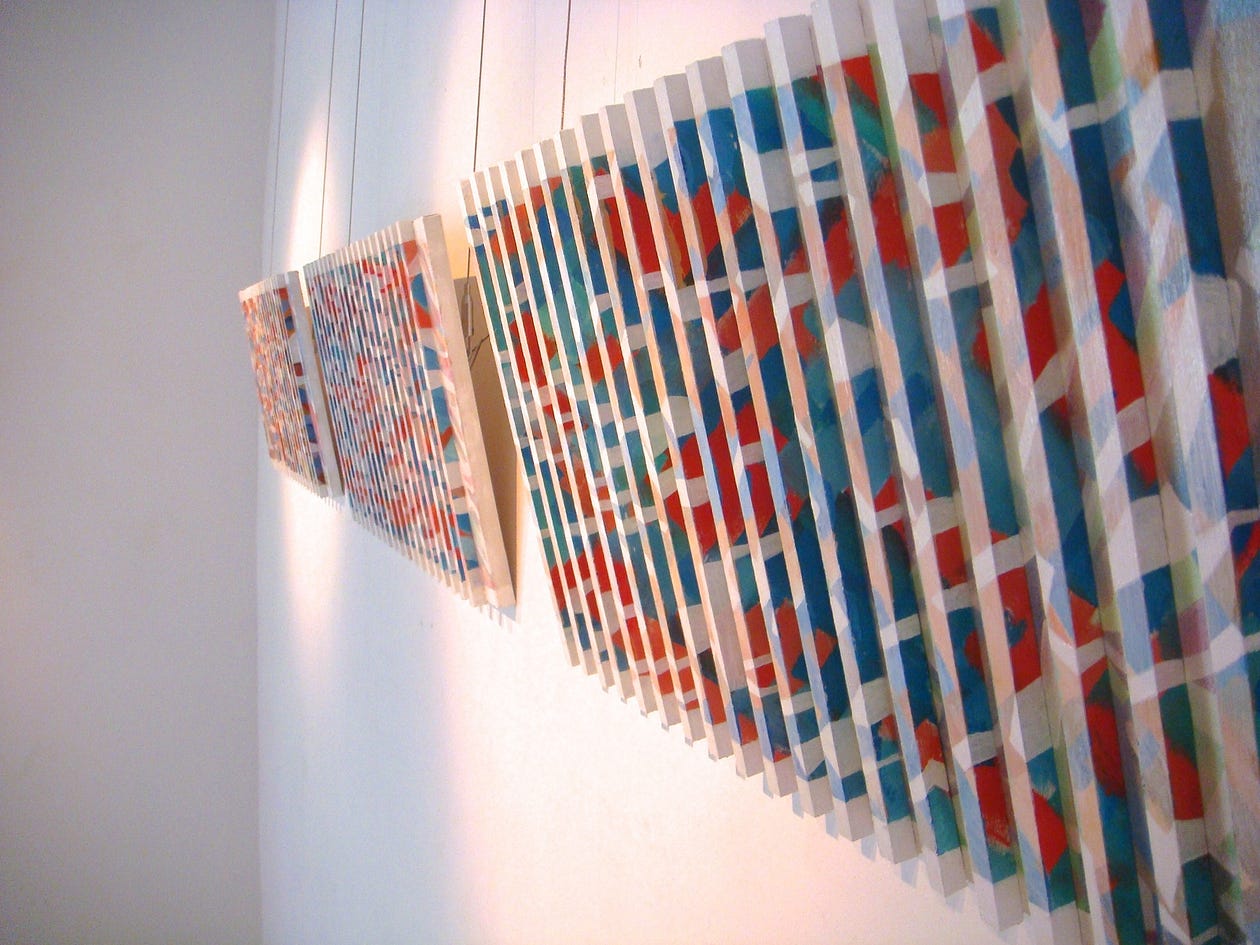

DART (Discovering and Receiving Transmissions) — The SUB Gallery, San Francisco

With DART, I initiated a new chapter in my artistic evolution: the construction of fully immersive environments where painting, space, and perception fused into a single experiential field. The exhibition transformed The SUB Gallery into a monochromatic ecosystem of mark-making, floor-to-ceiling murals rendered in your distinctive gestural style. By removing color almost entirely, the installation forced viewers to lean into subtler visual cues: edge contrasts, flicker effects, rhythm, and spatial ambiguity. The environment did not merely display imagery; it generated phenomena. Optical illusions emerged spontaneously in the viewer’s peripheral vision, while shifting patterns and phantom forms produced an experience that was actively co-created by the audience’s perceptual system. The exhibit’s title “Discovering and Receiving Transmissions” captured its conceptual premise: that the brain, when immersed in patterned information, begins to “listen” for meaning, treating abstract marks as signals, stories, or coded messages.

This was your first major exploration of art as an immersive perceptual technology, an installation that engaged neurological response as much as aesthetic appreciation.

DART was designed to activate mechanisms of pareidolia, predictive processing, pattern completion, and perceptual ambiguity, while using augmented reality to extend cognition beyond the physical installation. The human brain is evolutionarily tuned to detect meaning in noise, and the exhibit exploited this tendency by creating a richly ambiguous environment in which viewers’ perceptual expectations continually updated in real time. The monochrome palette heightened sensitivity to micro-contrasts, amplifying the brain’s reliance on internal predictions to make sense of the environment. When you layered augmented reality into the show, you introduced a second perceptual dimension, one that provided “transmissions” of additional narrative or symbolic content. The Augmented Reallity portion of the exhibit expanded the installation into a hybrid cognitive space where physical perception and digital imagination merged, demonstrating how technology can reveal latent narratives embedded within abstract imagery. Ultimately, DART functioned as a neurological playground, a training ground for perceptual flexibility, and a declaration that immersive art can serve as both aesthetic environment and cognitive apparatus; inviting viewers to discover not only new forms of visual meaning, but new capacities within themselves.

⸻

The Dance Within Fleeting Dreams — SOMArts, San Francisco

The Dance Within Fleeting Dreams was a fully interdisciplinary performance-art installation created and performed at SOMArts in San Francisco. Building on my exploration of immersive environments, this piece merged large-scale painted backdrops, live dance, and projected film into a single atmospheric experience. Inspired by Japanese Butoh, the performance followed a protagonist transitioning from waking life into a dream state and then struggling back into a strained, hyper-alert form of consciousness. The choreography emphasized emotional distortion, subtle gesture, and the liminal space between consciousness and imagination.

My signature mark-making style served as a visual architecture for the performance, with custom-painted backgrounds that set the tonal and psychological environment. The piece blurred the lines between painting, dance, and video art, allowing the visual language of his canvases to animate the performer’s movements and the projected film elements. The resulting interplay transformed the space into an embodied painting an artwork enacted in real time rather than confined to the wall.

The filmed component of The Dance Within Fleeting Dreams continued as a standalone museum installation following the live performance. Its hybrid form encouraged other artists and videographers to explore similar disciplinary overlaps, contributing to a growing movement of integrated performance-painting practices and expanding possibilities for immersive, multisensory storytelling.

Full Video of The Dance Within Fleeting Dreams

⸻

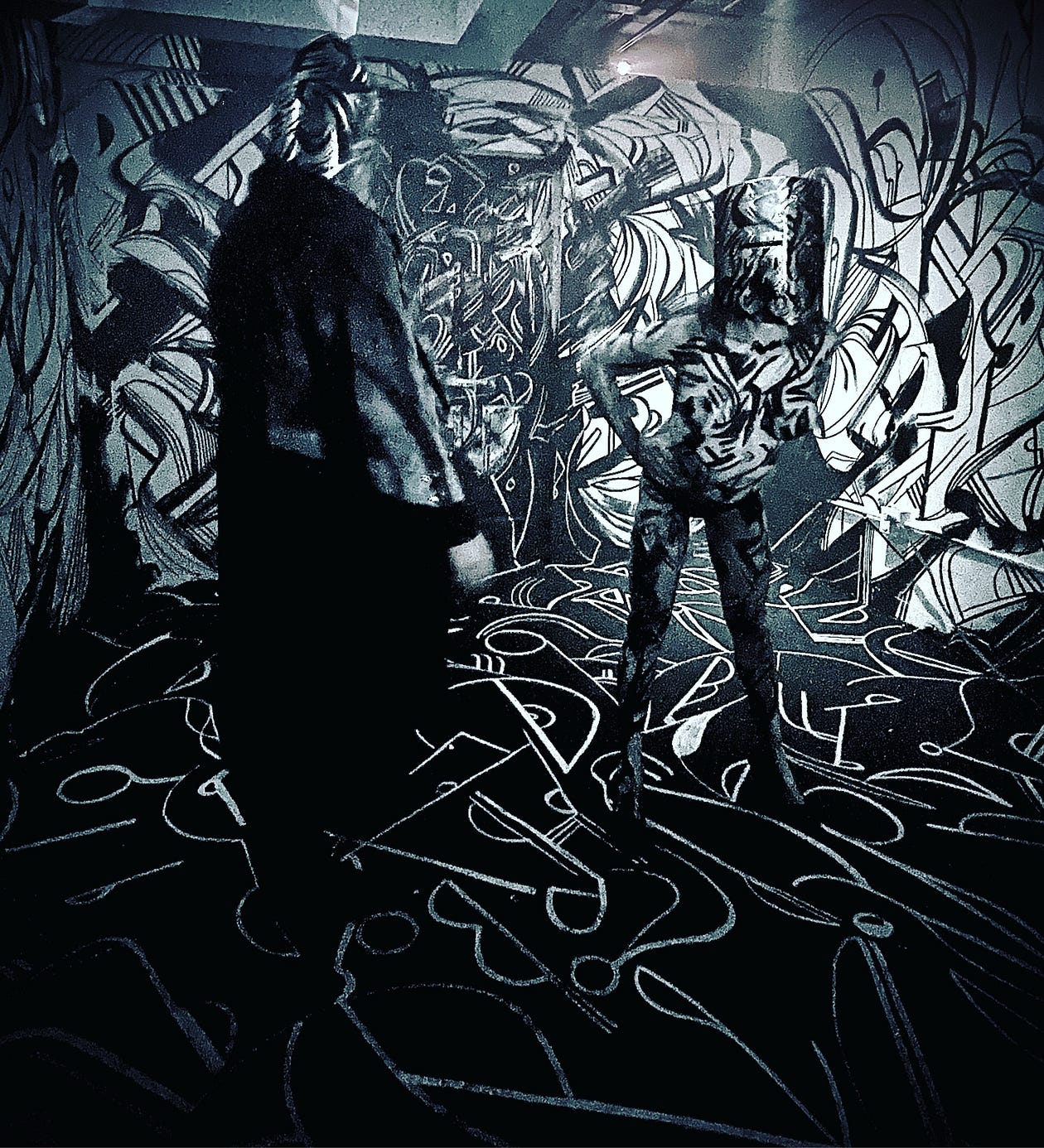

The Substance of Shadows — SCOGE, Lower East Side, Manhattan

The Substance of Shadows was an immersive, two-stage installation inspired by a line from The Hidden Way, my illustrated novel produced in 2022. Presented at SCOGE on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, the exhibition deepened my investigations into perceptual psychology, optical mark-making, and environmental storytelling. The work manipulated audience expectations through controlled sensory framing, using misdirection, contrast effects, and perceptual ambiguity to shift the viewer’s cognitive state as they moved from one space to the next.

Visitors first entered a room entirely wrapped in green velvet, an environment designed to limit visual complexity and induce a mild form of sensory monotony. This technique plays on the psychological principle of perceptual narrowing, which heightens sensitivity to change after prolonged exposure to uniform stimuli. The monochromatic setting convinced viewers that the exhibit was a conceptual exploration of color psychology and minimalism.

At the moment of perceived completion, participants were asked, “Have you seen the downstairs yet?” — a deliberate disruption of their cognitive map. This interruption functions as a schema violation, a known trigger for heightened attention and memory retention.

The hidden lower chamber revealed the true installation: an immersive black-and-white environment filled with densely layered calligraphic mark-making. Body-painted performers, whose headdresses and patterns matched the murals, created a live camouflage effect rooted in gestalt principles of figure — ground ambiguity. Viewers experienced shifting perceptual thresholds — figures dissolving into lines, lines becoming bodies, producing a sensation akin to pareidolia, where the mind imposes meaning on complex visual noise.

By staging the installation as a “double reveal,” The Substance of Shadows guided audiences through a controlled perceptual arc: from monotony to disruption, and finally into immersive overload. This arc mirrors cognitive models of liminality, in which transitional states allow for heightened receptivity and altered interpretation. The exhibition advanced my ongoing pursuit of experiences that merge optical art, embodied performance, and psychological engagement, placing the viewer inside the mechanics of perception itself.

⸻

The Substance of Shadows — Art Basel Performance Adaptation — Miami Beach

Following the success of The Substance of Shadows in New York, I was invited to bring an adapted, live-performance version of the work to Art Basel in Miami Beach. This iteration transformed the exhibition’s optical strategies into a ritualized, temporal performance involving body painting, movement, and environmental illusion. The piece emphasized embodiment, perceptual ambiguity, and the psychology of witnessing a transformation unfold in real time.

For this adaptation, I developed customized brushes and rollers inspired by indigenous body-painting techniques learned during his Amazonian field research for The Hidden Way. These tools allowed the live model’s body to be painted gradually throughout the evening, turning the performance into a durational ritual that aligned with principles of embodied cognition, the idea that perception and understanding emerge through physical participation and sensory interaction.

As the model changed poses and positions within the venue, the audience experienced a shifting perception of her form. The slow, sequential painting process leveraged the psychological phenomenon of attentional entrainment: observers unconsciously “sync” to the rhythm of repeated gestures, making the transformation feel more absorbing and meaningful. Each painted segment blurred the boundary between body and environment, echoing battleship camouflage principles and figure-ground reversal found in optical psychology.

The performance culminated in a final tableau in which the model, bound in Shibari rope, was positioned against a painted backdrop that matched the calligraphic patterns on her skin. This created a living optical illusion, a perceptual puzzle rooted in gestalt closure, pareidolia, and depth ambiguity, prompting the viewer to see body, line, structure, and environment shifting in and out of coherence.

By introducing live ritual, temporality, and embodied transformation, the Art Basel adaptation extended the psychological depth of The Substance of Shadows. The performance emphasized the audience’s active role in meaning-making through time, engaging mechanisms of perception that are rarely foregrounded in contemporary art events. This iteration marked a decisive expansion of my immersive practice, merging Amazonian-inspired techniques, optical mark-making, and psychological illusion into a single, continuously evolving work.

⸻

STOA — The Peristyle Rewilded — Prospect Park, Brooklyn

During this period, I founded STOA, a long-term, open-air artistic initiative dedicated to rewilding inspiration within an overlooked architectural relic at the southern edge of Prospect Park. The Peristyle, a columned structure evocative of the Parthenon yet largely unused by the city, became the physical and symbolic site for reviving the ancient idea of the STOA as a place for public thought, discourse, and creative exchange. This project transformed the forgotten space into a monthly exhibition venue where I presented my own work (at first) and invited artists from around the world to contribute. In doing so, STOA inverted the traditional expectation that audiences must seek out art in galleries, spaces that often reinforce social and cognitive gatekeeping and instead placed art back into the civic commons.

STOA operated at the intersection of environmental psychology, collective creativity, and public pedagogy. The Peristyle’s open-air structure fostered an atmosphere in which passersby encountered art without premeditation, activating the phenomenon of serendipitous attention; the unexpected cognitive shift that occurs when an unanticipated stimulus interrupts automated behavior. Research shows that public art in shared locations increases cognitive openness, social cohesion, and place attachment, all of which were central to STOA’s mission. By situating art in a democratic, non-institutional environment, I disrupted the psychological mechanisms that make museums feel exclusionary: threshold anxiety, evaluative apprehension, and culturally conditioned self-censorship.

As a “permaculture gallery,” STOA embodied principles of creative ecology, emphasizing sustainability, community nourishment, and the regenerative function of shared artistic ritual. Each exhibition operated like a seasonal growth cycle, emerging, decaying, and regenerating with a different set of works and collaborators. This cyclical rhythm encouraged ongoing participation and reinforced the idea that inspiration itself is a living ecosystem requiring cultivation. In a city whose gallery system often feels structurally restrictive, STOA has become a symbol of counter-environment: a free, open, evolving sanctuary where art could meet people where they already were.

Here is a more complete Article on the ongoing efforts of STOA with more photos and videos of the events:

⸻

The Chelsea Infiltration — New York City, 2024

By2024 I had become increasingly aware that my most innovative activations were occurring outside the sanctioned borders of the “established” art world. While visiting a friend’s exhibition in Chelsea (one of the most symbolically fortified, cost-prohibitive, and institutionally exclusive districts in contemporary art) I recognized an unusual opportunity: a gallery under renovation whose doors would remain unlocked throughout the weekend. Acting on an intuition honed through years of exploring artistic identity, spectacle, and psychological rupture, he returned on a Saturday with his paintings concealed in a large bag and quietly installed a full exhibition without permission.

Initially intended only as a guerrilla photoshoot, the act evolved over hours into a functioning, public-facing exhibition. I pinned the works under the gallery lights, curated the room as if it were his by right, and allowed the architecture of Chelsea’s prestige to refract his paintings into a new context. When I realized that no one questioned my presence because, psychologically, the power of spatial legitimacy outweighed suspicion, I opened the doors. Visitors wandered in assuming it was a sanctioned show. Many searched for the bar, made polite, formulaic compliments, or signed the provided sketchbook, participating unknowingly in a conceptual intervention about the rituals, blind spots, and social scripts of contemporary art openings. The exhibit lasted a single day, generated several online sales, and resulted in over half the pieces being collected, all before I packed the entire show back into my bag and disappeared into the night without detection.

The Chelsea Infiltration operated as a live experiment in institutional psychology, social perception, and the authority of space. Research shows that humans use environmental cues, architecture, location, signage, lighting, to determine legitimacy far more readily than interpersonal cues. By occupying a gallery in Chelsea, I leveraged the phenomenon of contextual validation, wherein the mere placement of an object within an “approved” setting raises its perceived value, credibility, and meaning. Visitors did not ask for credentials because the environment itself supplied them.

The performance also engaged the mechanisms of pluralistic ignorance and social conformity: attendees behaved as though they were at a typical opening because they assumed others shared the same understanding even when none of them had clear information. Their polite praise, brief engagement, and the recurring ritualistic search for alcohol mirrored the performative social behavior research identifies as characteristic of cultural prestige spaces. The invisible authorship that my presence as a silent observer rather than a declared artist amplified this effect, revealing how identity in such settings becomes a performative construct upheld by collective assumption rather than verified truth.

Ultimately, The Chelsea Infiltration was both an act of resistance and an anthropological probe into the psychology of the art world. It exposed the fragility of institutional authority, the ease with which perception can be manipulated, and the absurdity of gatekeeping practices that often privilege setting over substance. By temporarily occupying one of the world’s most coveted cultural battlegrounds and exiting without a trace I demonstrated that the true boundaries of contemporary art are cognitive, not architectural.

⸻

Nothing — ROTS Art Collective Collaboration, 2024

Inthe same year as The Chelsea Infiltration, I collaborated with the ROTS Art Collective to stage Nothing, an experiential, psychologically charged exhibition that invited participants to attend precisely what the invitation promised: nothing. The provocation worked. Over 400 people RSVP’d, and approximately 200 attended, drawn by the seductive paradox of an event defined by absence. Upon arrival, guests were greeted by hired paparazzi who photographed and interviewed them as though they were entering a high-profile cultural moment. The deliberate mismatch between external hype and internal emptiness was foundational to the piece’s conceptual architecture.

Guests rode an elevator upward in mounting anticipation, primed by the spectacle of celebrity treatment and the implied promise of exclusivity. Yet upon entering the venue, they found three consecutive rooms containing absolutely nothing; no artwork, no bar, no music, no lighting design beyond what was structurally necessary. A faint feedback hum lingered in the air, evoking the expectation that something was about to happen, but never would. The installation operated as a confrontation with perceptual voids and the human compulsion to fill them. When participants finally exited via a stairwell, they were met by Love, who interviewed them with the question: “Do you have something to say about nothing, or do you have nothing to say at all?”

Nothing was an active study in anticipatory cognition, meaning-making, and collective behavioral projection. The hype created by paparazzi triggered the “expectation effect,” wherein heightened external cues shape the participant’s internal experience. By then presenting a literal void, the exhibit forced attendees into direct contact with the psychological concept of apophenia, the tendency to impose meaning onto sparse or ambiguous stimuli. This effect was visibly demonstrated as some participants danced to nonexistent music, others sprawled on the floor, some sat in silent contemplation, and still others behaved as though they fully “understood” what nothing meant conceptually.

Observers watching their fellow attendees were often the most affected. Witnessing people respond to nothing revealed the phenomenon of social mirroring, where individuals look to others to determine how to behave in uncertain or unstructured environments. The piece also toyed with existential vacuum theory, where the absence of imposed meaning triggers either anxiety, creativity, or projected performance based on the participant’s psychological framework.

Ultimately, Nothing functioned as a satirical but deeply probing critique of art-world spectacle, audience expectation, and the human struggle with unmediated emptiness. By stripping an exhibition down to bare perception, we exposed the psychological scaffolding that audiences bring into cultural spaces and revealed how much of an art experience is constructed not by the artist, but by the viewer.

An more extensive article about this exhibit was published here NOTHING EXHIBIT

⸻

Instance

Location: Secret site in Soho & multiple locations across NYC, 2025

Instance was a guerrilla-style urban installation that unfolded across several months in New York City. The project began at a concealed workspace in Soho, where I produced large-scale black-and-white paintings on industrial tarp. Each finished work was then transported at night and stapled over the façade of an abandoned building in Chinatown, a site long associated with local graffiti writers and street-level visual culture.

Once installed, the tarps became open invitations for public intervention. Graffiti artists were encouraged, implicitly and explicitly, to tag, tear, overwrite, or repurpose the painted surfaces. Each week I returned to observe the state of the pieces. Whenever a tarp had accumulated new marks or damage, I removed it from the site and transported it to another location within the five boroughs, allowing the collaborative, parasitic life of the work to continue as it migrated across the city. New tarps were installed in its place, repeating the cycle.

Over the course of roughly three months, I discovered tarps re-installed by anonymous participants in unexpected locations — including Soho alleyways and derelict lots, demonstrating that the public had begun moving, transforming, and redistributing the work without prompting. Every installation, removal, and discovery was documented using 35mm film and time-lapse footage.

To mark each replacement, I hosted small, ephemeral “openings” on the sidewalk: a brief gathering where friends and invited guests stood beside the work, took photographs, and then dispersed for drinks or dinner. These hyper-temporary celebrations emphasized the project’s core concept: that each piece existed only in an instance; a fleeting moment of display, interaction, and disappearance captured solely through documentation.

Instance engaged with ideas of impermanence, authorship, and public intervention. By situating the work within an active graffiti environment and relinquishing control over its fate, the installation blurred the boundaries between contemporary art, urban folk expression, and participatory culture. The project’s unexpected audience response, especially the relocation of tarps by anonymous collaborators, revealed a collective desire to play with and reshape the work, transforming the city itself into a decentralized gallery.

A more complete write up of these Instances was Documented in the following article:

—

Epilogue

AsI reflect on these exhibitions and the philosophy that has guided them, I recognize that Epitheory is not merely a personal framework, it is a call to preserve and elevate the irreplaceable qualities of human experience. Each exhibition has been an effort to build a world that cannot be automated or simulated: a world shaped by human intention, human error, human intuition, and the nuanced choreography of bodies moving through space. In an era increasingly defined by artificial intelligence and synthetic stimuli, the role of the artist becomes not smaller, but more essential. We are the architects of experiences that machines cannot authentically replicate.

Epitheory is therefore more than a methodology; it is a reminder that art’s deepest resonance comes from its ability to shape perception through lived, sensory reality — from the texture of a surface, to the echo of footsteps in a gallery, to the unrepeatable emotional timbre of an individual encountering a story in physical space. My hope is that future generations of artists will not only continue making great work, but will also expand the complexity, intentionality, and narrative depth of the environments in which that work is encountered.

We are entering a cultural moment where simulations will grow ever more convincing, where virtual environments will mimic the real with increasing precision. Yet it is precisely for this reason that physical, spatial, human-crafted experiences will matter more than ever. The next great evolution in art will not be defined solely by digital possibility, but by the courage of artists to build atmospheres that exceed the logic of algorithms; to create exhibitions that breathe, transform, and imprint themselves upon the memory in ways no model can predict.

If Epitheory offers a contribution to that future, it is the insistence that exhibitions can be profound engines of meaning — places where story, genre, myth, and sensory encounter merge into something irreducibly human. My sincere hope is that the artists who follow will push these boundaries further, embracing ever richer complexities of theme, narrative, and experiential design, even as the world around them becomes more mediated by artificial systems.

The future of art belongs to those who dare to create experiences that cannot be downloaded, replicated, or generated: experiences that must be lived. If these exhibitions leave even a small imprint that helps guide that pursuit, then their purpose will have been fulfilled. My deepest hope is that the next generations will carry this impulse forward — building ever more intricate, resonant, and transformative artistic worlds for many years to come.

—

Harrison Love is Artist and Author of “The Hidden Way,” an award winning illustrated novel inspired by first hand interviews about Amazonian Myths and Folklore. He is also the Founder of the Permaculture Art Gallery STOA. More information about his Art and Writing can be found on www.harrisonlove.com

Video delving further into Harrison Love his life and his work:

—

Bibliography of References

The Red Door Gallery, The Rhode Island School of Design (RISD)

References:

• Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Books, 1959.

• Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Routledge, 1962.

- Arnheim, Rudolf. Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye. University of California Press, 1974.

—

Big Umbrella Gallery, San Francisco: The Pseudonym Experiments

References:

• Mead, George Herbert. Mind, Self, and Society. University of Chicago Press, 1934.

• Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Books, 1959.

• Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Aspen, no. 5–6, 1967.

- Turkle, Sherry. Life on the Screen: Identity in the Age of the Internet. Simon & Schuster, 1995.

—

Love Gallery, Denver: The Proxy Artist Experiment

References:

• Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. Routledge, 1990.

• Goffman, Erving. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. Anchor Books, 1959.

• Leary, Mark R., and June Price Tangney, eds. Handbook of Self and Identity. Guilford Press, 2003.

- Dennett, Daniel C. The Intentional Stance. MIT Press, 1987.

—

Persona Gallery, DUMBO: The Great Unmasking

References:

• Ekman, Paul. Emotions Revealed. Holt Paperbacks, 2007.

• Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Pantheon Books, 2012.

• Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books, 2011.

• boyd, danah. It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. Yale University Press, 2014.

- Berger, Jonah. Contagious: Why Things Catch On. Simon & Schuster, 2013.

—

RIND — John Erdos Gallery, Singapore

References

1. Alter, A. L., & Oppenheimer, D. M. (2009). Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 13(3), 219–235.

2. Botvinick, M. M. (2007). Conflict monitoring and decision making: Reconciling two perspectives on anterior cingulate function. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(4), 356–366.

3. Kaplan, J. T., & Oudeyer, P. Y. (2007). In search of the neural correlates of curiosity. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(8), 381–387.

4. van Steenbergen, H. (2015). Affective chronometry in cognitive control: Pitfalls and advances. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 794.

5. Zald, D. H. (2003). The human amygdala and the emotional evaluation of sensory stimuli. Brain Research Reviews, 41(1), 88–123.

6. Vartanian, O. & Goel, V. (2004). Neuroanatomical correlates of aesthetic preference for paintings. NeuroReport, 15(5), 893–897.

—

RED RUM — The New School Gallery, Singapore

References

1. Hsee, C. K., & Ruan, B. (2016). The Pandora Effect: The power and peril of curiosity. Psychological Science, 27(5), 659–666.

2. McCoy, A. N., & Platt, M. L. (2005). Risk-sensitive neurons in macaque posterior cingulate cortex. Nature Neuroscience, 8(9), 1220–1227.

3. Pessoa, L., & Adolphs, R. (2010). Emotion processing and the amygdala: Integrating findings. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20(2), 150–155.

4. Vartanian, O. (2014). Neural bases of emotion — aesthetic interactions in the experience of art. Progress in Brain Research, 204, 243–258.

5. Zuckerman, M. (1994). Behavioral expressions and biosocial bases of sensation seeking. Cambridge University Press.

6. van Steenbergen, H., Band, G. P., & Hommel, B. (2009). Reward counteracts conflict adaptation. Psychological Science, 20(12), 1473–1477.

—

BEYOND THE STREETS — Los Angeles & California (Collaboration with Shepard Fairey and Others)

References

1. Kaplan, S. (1995). The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 15(3), 169–182.

2. Carr, S., Rivlin, L. G., & Lang, M. H. (1992). Public Space. Cambridge University Press.

3. Berlyne, D. E. (1971). Aesthetics and Psychobiology. Appleton-Century-Crofts.

4. Zajonc, R. B. (1968). Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 9(2), 1–27.

5. Somerville, L. H., & Casey, B. J. (2010). Developmental neurobiology of cognitive control and motivational systems. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 20(2), 236–241.

6. Vartanian, O. (2014). Neural bases of emotion — aesthetic interactions in the experience of art. Progress in Brain Research, 204, 243–258.

—

RIOT / PROTEST SERIES — The SUB Gallery, San Francisco (2015)

References

1. Durkheim, É. (1912/1995). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Free Press.

2. Van Zomeren, M., Postmes, T., & Spears, R. (2008). Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action. Psychological Bulletin, 134(4), 504–535.

3. Piff, P. K., Dietze, P., Feinberg, M., Stancato, D. M., & Keltner, D. (2015). Awe, the small self, and collective engagement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 883–899.

4. Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

5. Anderson, C., & Galinsky, A. D. (2006). Power, optimism, and risk-taking. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36(4), 511–536.

6. Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Harvard University Press.

—

RIOT / PROTEST SERIES — The SUB Gallery, San Francisco (2015)

References

1. Gilbert, D. T., & Wilson, T. D. (2007). Prospection: Experiencing the future. Science, 317(5843), 1351–1354.

2. Haidt, J. (2012). The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. Vintage.

3. Hardin, G. (1968). The tragedy of the commons. Science, 162(3859), 1243–1248.

4. Tuan, Y.-F. (1977). Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press.

5. Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230.

6. Varnum, M. E., & Grossmann, I. (2017). Cultural change: The how and the why. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 956–972.

—

DART (Discovering and Receiving Transmissions) — The SUB Gallery, San Francisco

References

1. Gregory, R. L. (1997). Knowledge in perception and illusion. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 352(1358), 1121–1127.

2. Clark, A. (2013). Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 36(3), 181–204.

3. Liu, T., & Chaudhuri, A. (1995). Recognition of hidden forms. Nature, 373(6515), 273–275.

4. Martínez-Conde, S., Macknik, S. L., & Hubel, D. H. (2004). The role of fixational eye movements in visual perception. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(3), 229–240.

5. Slater, M. (2018). Immersion and the illusion of presence in VR. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 373(1758).

6. Raskar, R., & Bimber, O. (2005). Spatial Augmented Reality: Merging Real and Virtual Worlds. CRC Press.

—

The Substance of Shadows — SCOGE, Lower East Side, Manhattan

References

1. Perceptual Narrowing & Sensory Adaptation

• Clifford, C. W. G., & Webster, M. A. (Eds.). Adaptation and Perception: The Psychophysics of Human Perception.

• Wark, B., Lundstrom, B. N., & Fairhall, A. L. “Sensory adaptation.” Current Opinion in Neurobiology.

2. Schema Violation & Attention Response

• Van Petten, C., & Luka, B. J. “Prediction, priming, and the P300.” Psychophysiology.

• Schank, R. & Abelson, R. Scripts, Plans, Goals, and Understanding.

3. Figure — Ground Ambiguity & Gestalt Principles

• Palmer, S. E. Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology.

• Wertheimer, M. “Laws of Organization in Perceptual Forms.” Psychologische Forschung.

4. Pareidolia & Meaning-Making Under Ambiguity

• Liu, J. et al. “Seeing Jesus in toast: Neural and behavioral correlates of face pareidolia.” Cortex.

• Brugger, P. “From haunted brain to haunted science.” Cognitive Neuropsychiatry.

5. Liminality & Perceptual Transition States

• Turner, V. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure.

• Thomassen, B. “The Uses and Meanings of Liminality.” International Political Anthropology.

—

The Substance of Shadows — Art Basel Performance Adaptation — Miami Beach

References

1. Embodied Cognition & Ritualized Transformation

• Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. The Embodied Mind.

• McNeill, W. H. Keeping Together in Time: Dance and Drill in Human History.

2. Attentional Entrainment & Temporal Synchrony

• Large, E. W., & Jones, M. R. “The dynamics of attending.” Psychological Review.

• Lakatos, P. et al. “Entrainment of neuronal oscillations as a mechanism of attentional selection.” Science.

3. Figure — Ground Ambiguity & Camouflage Perception

• Palmer, S. E. Vision Science: Photons to Phenomenology.

• Stevens, M., & Merilaita, S. Animal Camouflage: Mechanisms and Function.

4. Pareidolia & Ambiguous Body/Space Perception

• Liu, J. et al. “Pareidolia and face-like pattern detection.” Cortex.

• Brugger, P. “Belief and illusion in the perception of ambiguous stimuli.” Cognitive Neuropsychiatry.

5. Gestalt Closure & Depth Ambiguity in Illusory Spaces

• Koffka, K. Principles of Gestalt Psychology.

- Kellman, P. J. & Shipley, T. F. “A theory of visual interpolation.” Psychological Review.

—

STOA — The Peristyle Rewilded — Prospect Park, Brooklyn

References

1. Environmental Psychology & Public Space Engagement

• Kaplan, R. & Kaplan, S. The Experience of Nature: A Psychological Perspective.

• Carr, S., Francis, M., Rivlin, L., & Stone, A. Public Space.

2. Serendipitous Attention & Cognitive Openness

• Csikszentmihalyi, M., & Robinson, R. E. The Art of Seeing: An Interpretation of the Aesthetic Encounter.

• Berlyne, D. E. “Aesthetics and psychobiology.” Science Editions.

3. Place Attachment & Social Cohesion Through Art

• Lewicka, M. “Place attachment: How far have we come?” Journal of Environmental Psychology.

• Markusen, A. & Gadwa, A. Creative Placemaking.

4. Creative Ecology & Regenerative Artistic Systems

• Guattari, F. The Three Ecologies.

• Hagoort, G. “Cultural entrepreneurship and creative ecology.” International Journal of Cultural Policy.

5. Threshold Anxiety & Museum Gatekeeping

• Macdonald, S. A Companion to Museum Studies.

• Bourdieu, P., & Darbel, A. The Love of Art: European Art Museums and Their Public.

—

The Chelsea Infiltration — New York City, 2024

References

1. Contextual Validation & Authority of Space

• Zimbardo, P. The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil. (Ch. on situational power)

• Kirk, J. H., & Sellen, A. “On the cognitive authority of environments.” Cognitive Science Review.

2. Pluralistic Ignorance & Social Conformity

• Cialdini, R. B. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion.

• Prentice, D. & Miller, D. “Pluralistic ignorance and social norms.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

3. Performative Behavior in Prestige Spaces

• Thornton, S. Seven Days in the Art World.

• Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste.

4. Institutional Critique & Invisible Authorship

• Fraser, A. “From the Critique of Institutions to an Institution of Critique.” Artforum.

- Goffman, E. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life.

—

Nothing — ROTS Art Collective Collaboration, 2024

References

1. Expectation Effect & Anticipatory Cognition

• Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the Classroom: Teacher Expectation and Pupils’ Intellectual Development.

• Olson, J. M., Roese, N. J. “Expectancies.” Handbook of Social Psychology.

2. Apophenia & Meaning-Making Under Ambiguity

• Brugger, P. “From Haunted Brain to Haunted Science: A Cognitive Neuroscience View of Paranormal Experience.” Cognitive Neuropsychiatry.

• Fyfe, H. & Biddle, S. “Perceiving Patterns in Noise: Apophenia and Human Cognition.”

3. Social Mirroring & Ambiguous Environments

• Sherif, M. “A Study of Some Social Factors in Perception.” Archives of Psychology.

• Asch, S. E. “Opinions and Social Pressure.” Scientific American.

4. Existential Vacuum & Behavioral Projection

• Frankl, V. Man’s Search for Meaning.

- Yalom, I. Existential Psychotherapy.

—